Latest news from the lab

When does imagery require motor resources? A commentary on Bach et al., 2022

In press

Psychological Research

Gilles Vannuscorps

In their article "Why motor imagery is not really motoric: towards a re-conceptualization in terms of effect-based action control" (Psychological Research, 2002), Bach, Frank, and Kunde introduced a hypothesis that encompasses two main claims: (1) motor imagery relies primarily on representations of the perceptual effects of actions, and (2) the engagement of motor resources provides access to the spe‑ cific timing, kinematic or internal bodily state that characterize an action. In this commentary, I argue that the first claim is compelling and suggest some alternatives to the second one.

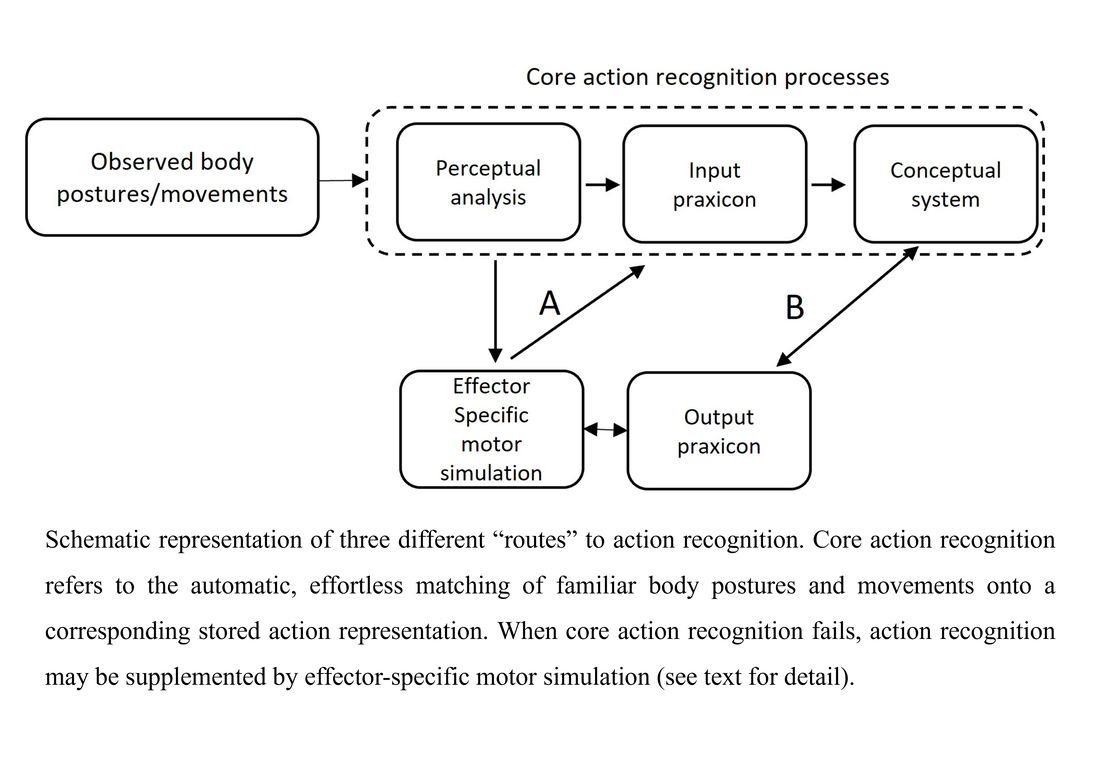

Effector-specific motor simulation supplements core action recognition processes in adverse conditions

In press

Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience

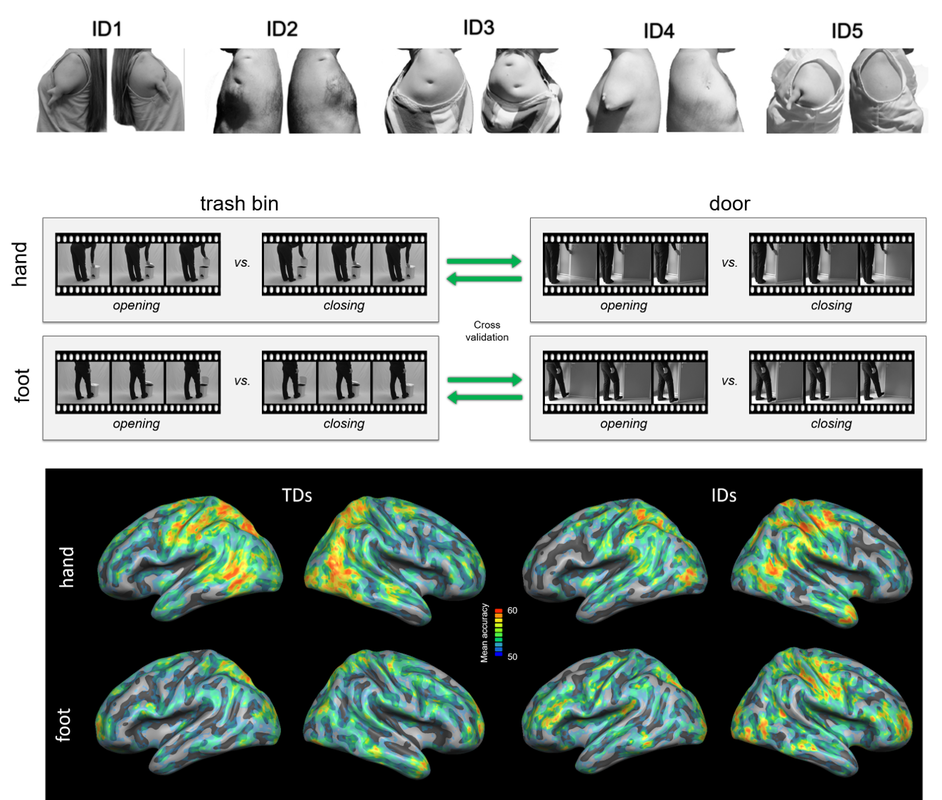

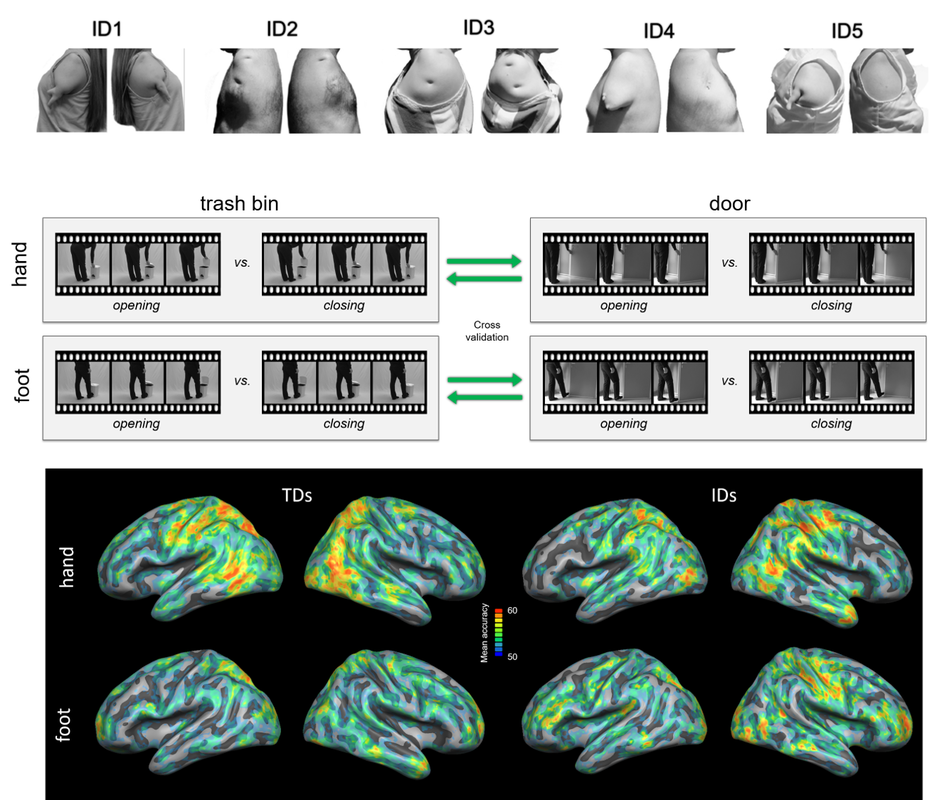

Gilles Vannuscorps & Alfonso Caramazza

|

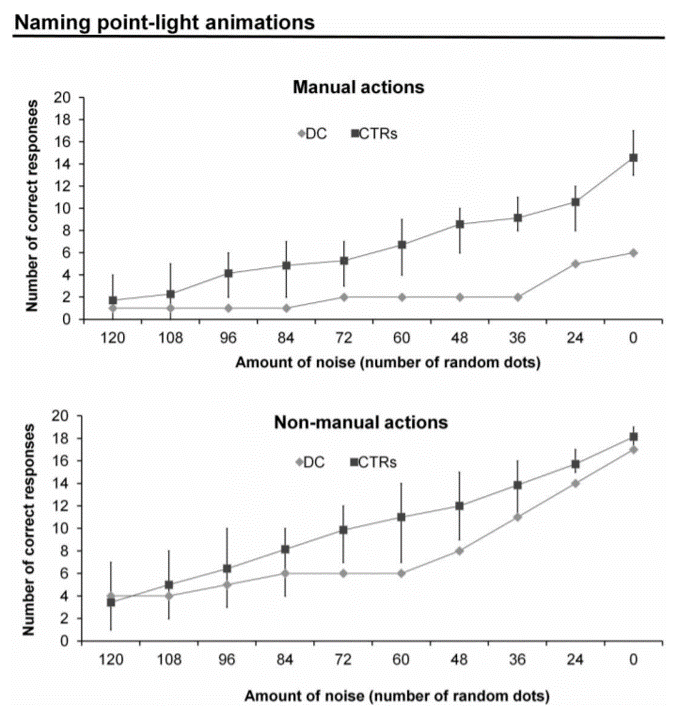

Observing other people acting activates imitative motor plans in the observer. Whether, and if so when and how, such “effector-specific motor simulation” contributes to action recognition remains unclear. We report that individuals born without upper limbs (IDs) – who cannot covertly imitate upper limb movements – are significantly less accurate at recognizing degraded (but not intact) upper-limb than lower-limb actions (i.e., point-light animations). This finding emphasizes the need to reframe the current controversy regarding the role of effector-specific motor simulation in action recognition: instead of focusing on the dichotomy between motor and non-motor theories, the field would benefit from new hypotheses specifying when and how effector-specific motor simulation may supplement core action recognition processes to accommodate the full variety of action stimuli that humans can recognize.

|

From intermediate shape-centered representations to the perception of oriented shapes: response to commentaries

August 29, 2023

Cognitive Neuropsychology

Gilles Vannuscorps, Albert Galaburda & Alfonso Caramazza

In this response paper, we start by addressing the main points made by the commentators on the target article’s main theoretical conclusions: the existence and characteristics of the intermediate shape-centered representations (ISCRs) in the visual system, their emergence from edge detection mechanisms operating on different types of visual properties, and how they are eventually reunited in higher order frames of reference underlying conscious visual perception. We also address the much-commented issue of the possible neural mechanisms of the ISCRs. In the final section, we address more specific and general comments, questions, and suggestions which, albeit very interesting, were less directly focused on the main conclusions of the target paper.

Atypical influence of biomechanical knowledge in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome-Towards a different perspective on body representation

January 10, 2023

Scientific Reports

L. Filbrich, C. Verfaille, G. Vannuscorps, A. Berquin, O. Barbier, X. Libouton, V. Fraselle, D. Mouraux & V. Legrain

|

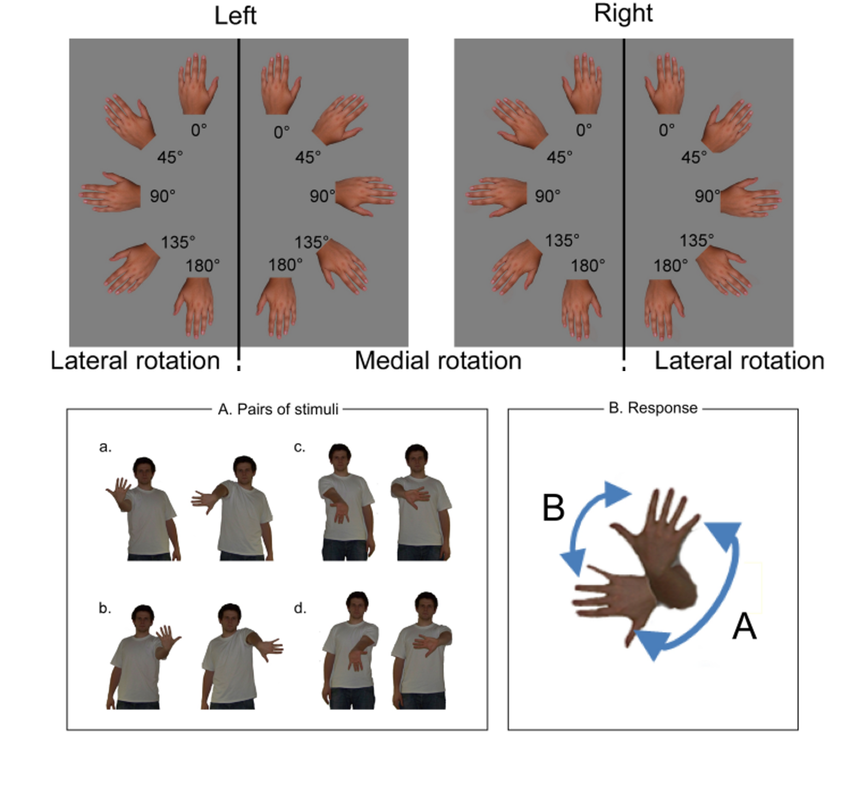

Part of the multifaceted pathophysiology of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is ascribed to lateralized maladaptive neuroplasticity in sensorimotor cortices, corroborated by behavioral studies indicating that patients present difficulties in mentally representing their painful limb. Such difficulties are widely measured with hand laterality judgment tasks (HLT), which are also used in the rehabilitation of CRPS to activate motor imagery and restore the cortical representation of the painful limb. The potential of these tasks to elicit motor imagery is critical to their use in therapy, yet, the influence of the body’s biomechanical constraints (BMC) on HLT reaction time, supposed to index motor imagery activation, is rarely verified. Here we investigated the influence of BMC on the perception of hand postures and movements in upper-limb CRPS. Patients were slower than controls in judging hand laterality, whether or not stimuli corresponded to their painful hand. Reaction time patterns reflecting BMC were mostly absent in CRPS and controls. A second experiment therefore directly investigated the influence of implicit knowledge of BMC on hand movement judgments. Participants judged the perceived path of movement between two depicted hand positions, with only one of two proposed paths that was biomechanically plausible. While the controls mostly chose the biomechanically plausible path, patients did not. These findings show non-lateralized body representation impairments in CRPS, possibly related to difficulties in using correct knowledge of the body’s biomechanics. Importantly, they demonstrate the challenge of reliably measuring motor imagery with the HLT, which has important implications for the rehabilitation with these tasks.

|

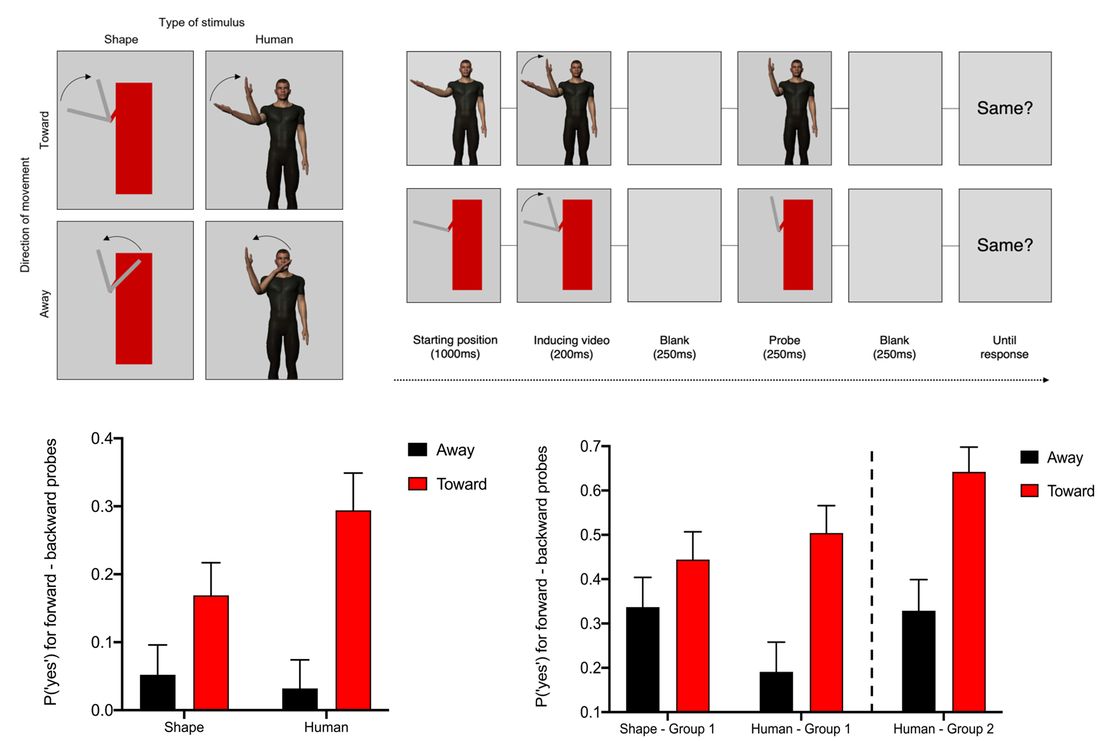

Predictive extrapolation of observed body movements is tuned by knowledge of the body biomechanics

October 7, 2022

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance

Antoine Vandenberghe & Gilles Vannuscorps

|

After a moving object has disappeared, observers typically mislocate its final position to where that object would have been if it had briefly continued to move. Previous studies have shown that this “forward displacement” (FD) is significantly smaller when observers see an upper-limb movement directed away from the body that would have been biomechanically impossible to continue along the same trajectory after it has disappeared than when the movement is directed toward the body and would have been easy to continue. This finding has been argued to reflect an implicit influence of observers’ biomechanical knowledge on FD. However, this effect could also result from a “landmark attraction”, which has been shown to reduce the size of displacement when an object moves away, rather than toward, from a landmark. To discriminate these possibilities, we measured the FD elicited by arm movements directed away or toward the body, which would have been biomechanically impossible or easy to continue after the stimuli disappeared, and by highly similar movements of geometrical shapes. In two experiments, we found a significantly larger effect of movement direction for the human stimuli. Thus, knowledge of the body biomechanics influences FD for body movements.

|

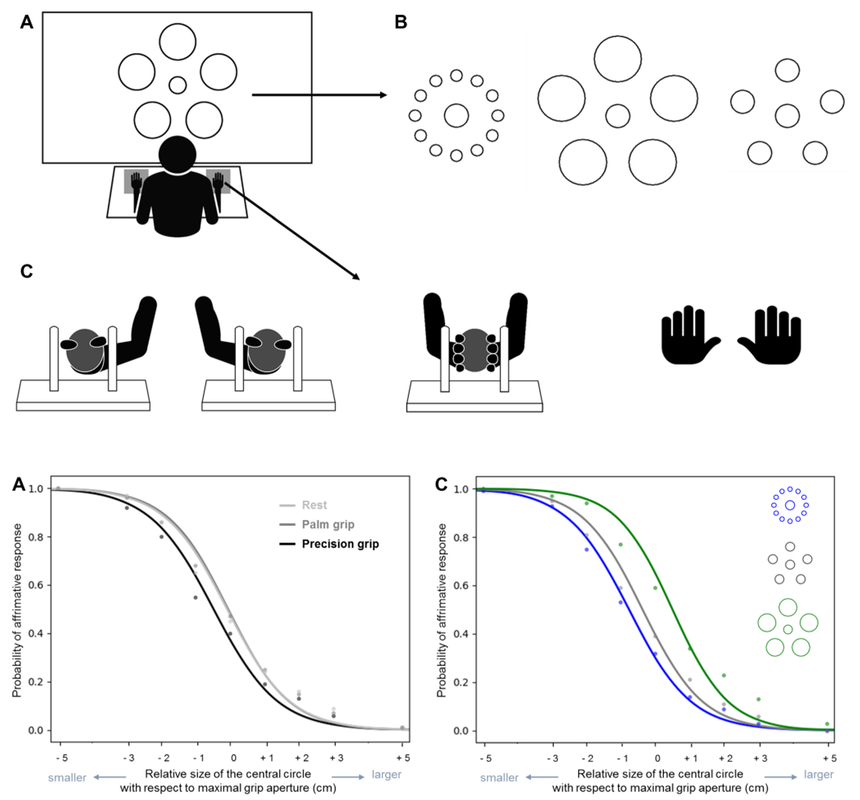

Selective interference of hand posture with grasping capability estimation

November 1, 2021

Experimental Brain Research

Laurie Geers, Gilles Vannuscorps, Mauro Pesenti & Michael Andres

|

Previous studies have shown that judgments about how one would perform an action are affected by the current body posture. Hence, judging one's capability to grasp an object between index and thumb is influenced by their aperture at the time of the judgment. This finding can be explained by a modification of the internal representation of one’s hand through the effect of sensorimotor input. Alternatively, the influence of grip aperture might be mediated by a response congruency effect, so that a “less” vs. “more” open grip would bias the judgment toward a “less” vs. “more” capable response. To specify the role of sensorimotor input in prospective action judgments, we asked participants to estimate their capability to grasp circles between index and thumb while performing a secondary task that requires them to squeeze a ball with these two fingers (precision grip) or with a different hand configuration (palm grip). Experiment 1 showed that participants underestimated their grasping capability when the squeezing task involved the same grip as the judged action (precision grip) and their estimates were bound to the relative size of objects as revealed by size-contrast illusions (Ebbinghaus). Experiment 2 showed that the grip reduction caused by the squeezing task also interfered with the discrimination of large numbers in magnitude judgments, but this incongruency effect was only observed for the palm grip. The dissociated effects of the two grips in graspability and numerical judgments indicate that sensorimotor input may affect the perceived ability to grasp objects, independently of response congruency, by modifying the representation of the hand in action.

|

The form of reference frames in vision: the case of intermediate shape-centered representations

October 5, 2021

Neuropsychologia

Gilles Vannuscorps, Albert Galaburda & Alfonso Caramazza

|

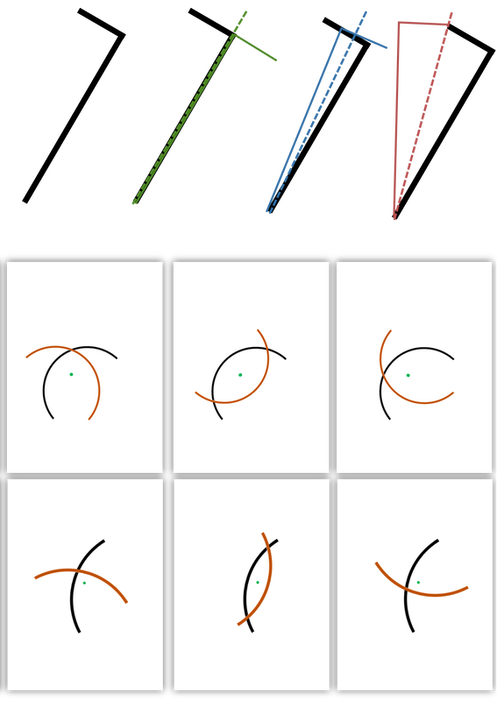

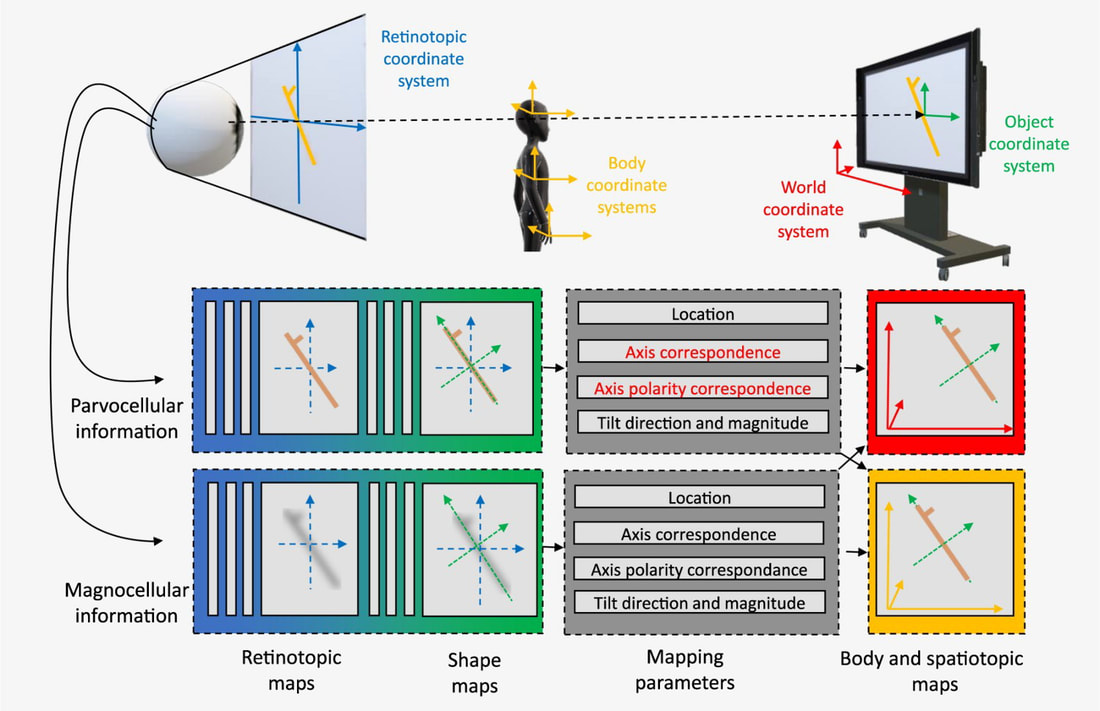

Although a great deal is known about the early sensory and the later, perceptual, stages of visual processing, far less is known about the nature of intermediate representational units and reference frames. Progress in understanding intermediate levels of representations in vision is hindered by the complexity and interactions between multiple levels of representation in the visual system, making it difficult to isolate and study the nature of one particular level. Nature occasionally provides the opportunity to peer inside complex systems by isolating components of a system through accidental damage or genetic modification of neural components. We have recently reported the case of a young woman who perceives 2D bounded regions of space as if they were plane-rotated by 90, 180 or 270 degrees around their center, mirrored across their own axes, or both. This suggested that an intermediate stage of processing consists in representing mutually exclusive 2D bounded regions extracted from the retinal image in their own “shape-centered” perceptual frame. We proposed to refer to this level of representation as “intermediate shape-centered representation” (ISCR). Here, we used Davida’s pattern of errors across 9 experiments as a tool for specifying in greater detail the geometrical properties of the reference frame in which elongated and/or symmetrical shapes are represented at the level of the ISCR. The nature of Davida’s errors in these experiments suggests that ISCRs are represented in reference frames composed of orthogonal axes aligned and centered onto the most elongated segment of elongated shapes and, for symmetrical shapes deprived of a straight segment, aligned to their axis of symmetry, and centered on their centroid.

|

Shape-centered representations of bounded regions of space mediate the perception of objects

August 24, 2021

Cognitive Neuropsychology

Gilles Vannuscorps, Albert Galaburda & Alfonso Caramazza

|

We report the study of a woman who perceives 2D bounded regions of space (“shapes”) defined by sharp edges of medium to high contrast as if they were rotated by 90, 180 degrees around their centre, mirrored across their own axes, or both. In contrast, her perception of 3D, strongly blurred or very low contrast shapes, and of stimuli emerging from a collection of shapes, is intact. This suggests that a stage in the process of constructing the conscious visual representation of a scene consists of representing mutually exclusive bounded regions extracted from the initial retinotopic space in “shape-centered” frames of reference. The selectivity of the disorder to shapes originally biased toward the parvocellular subcortical pathway, and the absence of any other type of error, additionally invite new hypotheses about the operations involved in computing these “intermediate shape-centered representations” and in mapping them onto higher frames for perception and action.

|

Shifting attention in visuospatial short-term memory does not require oculomotor planning: insight from congenital gaze paralysis

October 15, 2021

Neuropsychologia

Nicolas Masson, Michael Andres, Sarah Carneiro Pereira, Antoine Vandenberghe, Mauro Pesenti & Gilles Vannuscorps

|

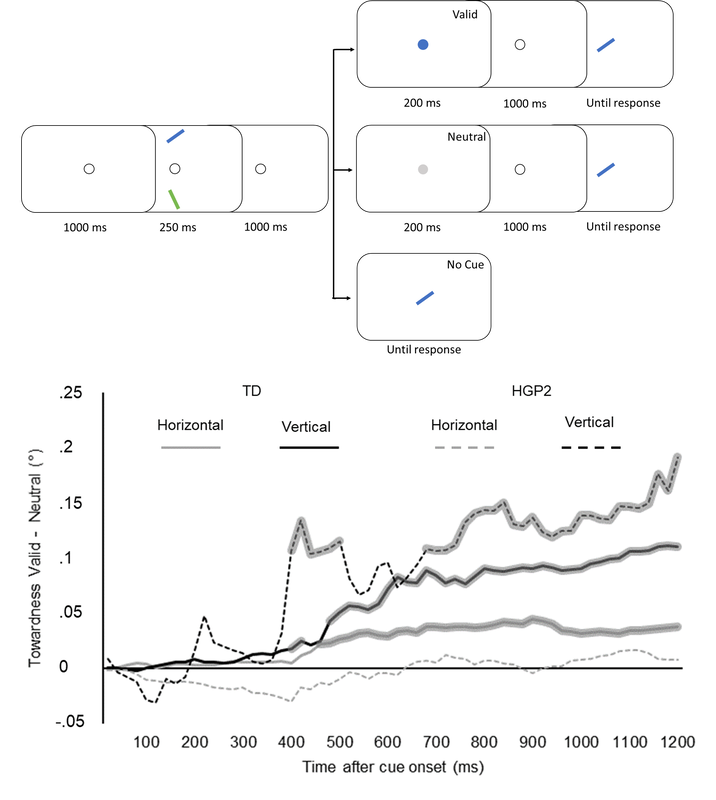

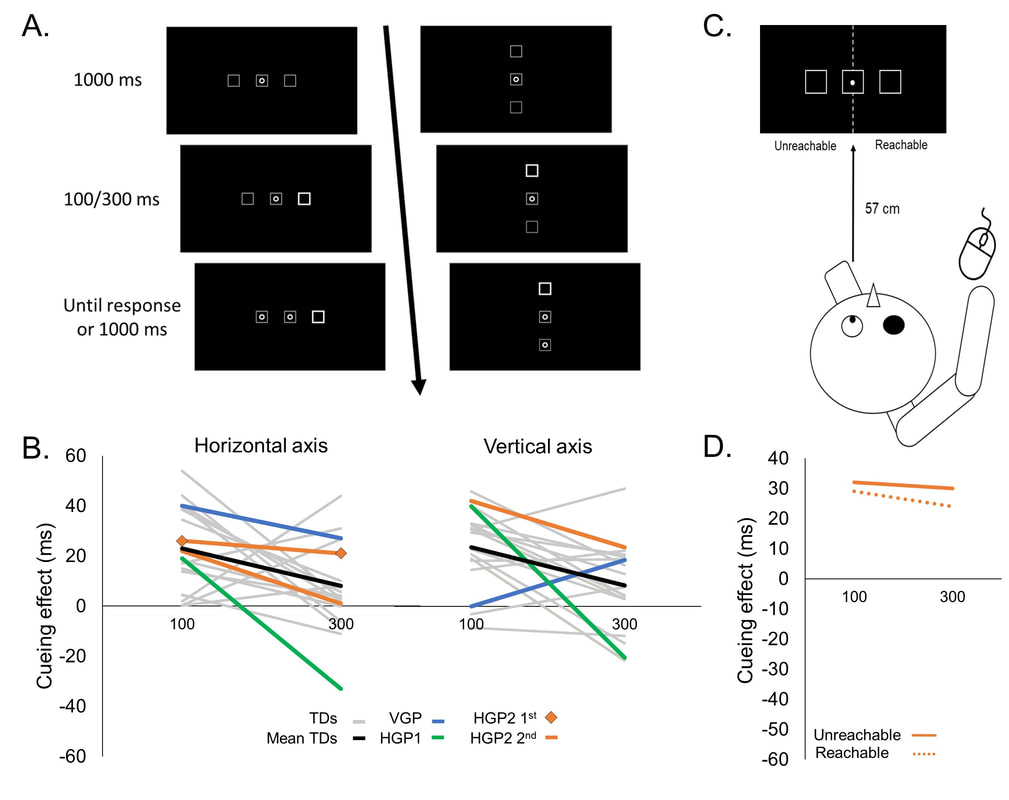

Attention allows pieces of information stored in visuospatial short-term memory (VSSTM) to be selectively processed. Previous studies showed that internal shifts of attention in VSSTM in response to a retro-cue are accompanied by eye movements in the direction of the position of the memorized item although there is nothing left to look at. This finding raises the possibility that internal shifts of attention in VSSTM are underpinned by mechanisms originally involved in the planning and control of eye movements. To explore this possibility, we investigated the ability of an individual with congenital horizontal gaze paralysis (HGP2) to shift her attention horizontally or vertically toward a memorized item within VSSTM using a retro-cue paradigm. As efficient oculomotor programming is not innate but requires some trial and error learning and adaptation to develop, congenital paralysis prevents this development. Consequently, if shifts of attention in VSSTM rely on the same mechanisms as those supporting the programming of eye movements, then horizontal congenital gaze paralysis should necessarily prevent typical retro-cueing effect in the paralyzed axis. At odds with this prediction, HGP2 showed a typical retro-cueing effect in her paralyzed axis. This original finding indicates that selecting an item within VSSTM is not made by saccade programming and that it does not depend on the ability to program it.

|

Typically efficient lipreading without motor simulation

November 15, 2020

|

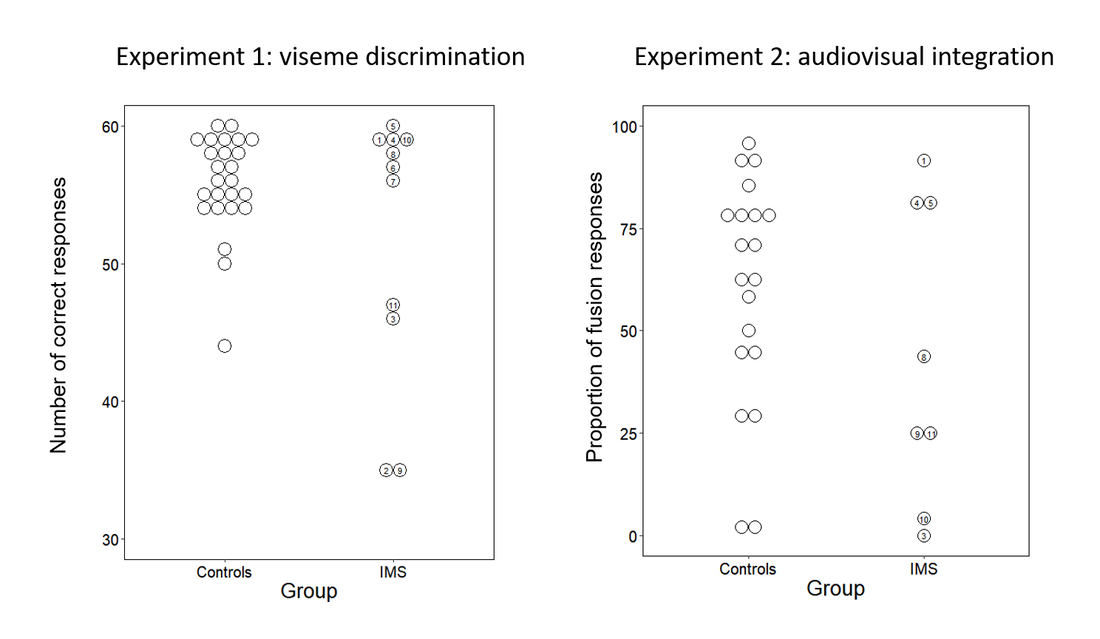

All it takes is a face to face conversation in a noisy environment to realize that viewing a speaker’s lip movements contributes to speech comprehension. What are the processes underlying the perception and interpretation of visual speech? Brain areas that control speech production are also recruited during lip reading. This finding raises the possibility that lipreading may be supported, at least to some extent, by a covert unconscious imitation of the observed speech movements in the observer’s own speech motor system – a motor simulation. However, whether, and if so to what extent motor simulation contributes to visual speech interpretation remains unclear. In two experiments, we found that several participants with congenital facial paralysis were as good at lipreading as the control population and performed these tasks in a way that is qualitatively similar to the controls despite severely reduced or even completely absent lip motor representations. Although it remains an open question whether this conclusion generalizes to other experimental conditions and to typically developed participants, these findings considerably narrow the space of hypothesis for a role of motor simulation in lip-reading. Beyond its theoretical significance in the field of speech perception, this finding also calls for a re-examination of the more general hypothesis that motor simulation underlies action perception and interpretation developed in the frameworks of motor simulation and mirror neuron hypotheses.

|

Evidence for an effector-independent action system from people born without hands

October 26, 2020

|

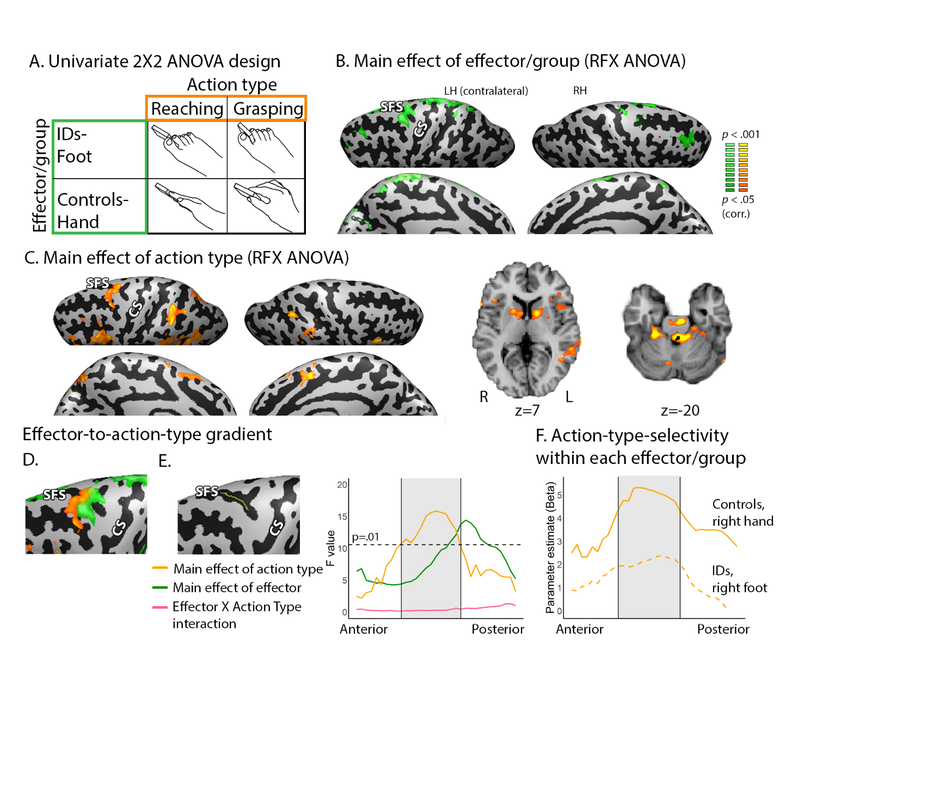

Many parts of the visuomotor system guide daily hand actions like reaching for and grasping objects. Do these regions depend exclusively on the hand as a specific body part whose movement they guide, or are they organized for the reaching task per se, for any body part used as an effector? To address this question, we conducted a neuroimaging study with people born without upper limbs—individuals with dysplasia—who use the feet to act, as they and typically-developed controls performed reaching and grasping actions with their dominant effector. Individuals with dysplasia have no prior experience acting with hands, allowing us to control for hand motor imagery when acting with another effector (i.e. foot). Primary sensorimotor cortices showed selectivity for the hand in controls and foot in individuals with dysplasia. Importantly, we found a preference based on action type (reaching /grasping) regardless of the effector used in the association sensorimotor cortex, in the left intraparietal sulcus and dorsal premotor cortex, as well as in the basal ganglia and anterior cerebellum. These areas also showed differential response patterns between action types for both groups. Therefore, frontoparietal motor association areas showed effector-independent action-type representation. Intermediate areas along a posterior-anterior gradient in the left dorsal premotor cortex gradually transitioned from selectivity based on the body part to action type. These findings indicate that some visuomotor association areas are organized based on abstract action functions independent of specific sensorimotor parameters, suggesting a hierarchical organization from effector-dependent to effector-independent functions.

|

Exogenous covert shift of attention without the ability to plan eye movements

August 11, 2020

|

The automatic allocation of attention to a salient stimulus in the visual periphery (e.g., a traffic light turning red) while maintaining fixation elsewhere (e.g., on the car ahead) is referred to as exogenous covert shift of attention (ECSA). An influential explanation is that ECSA results from the programming of a saccadic eye movement toward the stimulus of interest, although the actual movement may be withheld if needed. In this paper, however, we report evidence of ECSA in the paralyzed axis of three individuals with either horizontal or vertical congenital gaze paralysis, including for stimuli appearing at locations that cannot be foveated through head movements. This demonstrates that ECSA does not require programming either eye or head movements and calls for a re-examination of the oculomotor account.

|

Efficient recognition of facial expressions does not require motor simulation

May 5, 2020

|

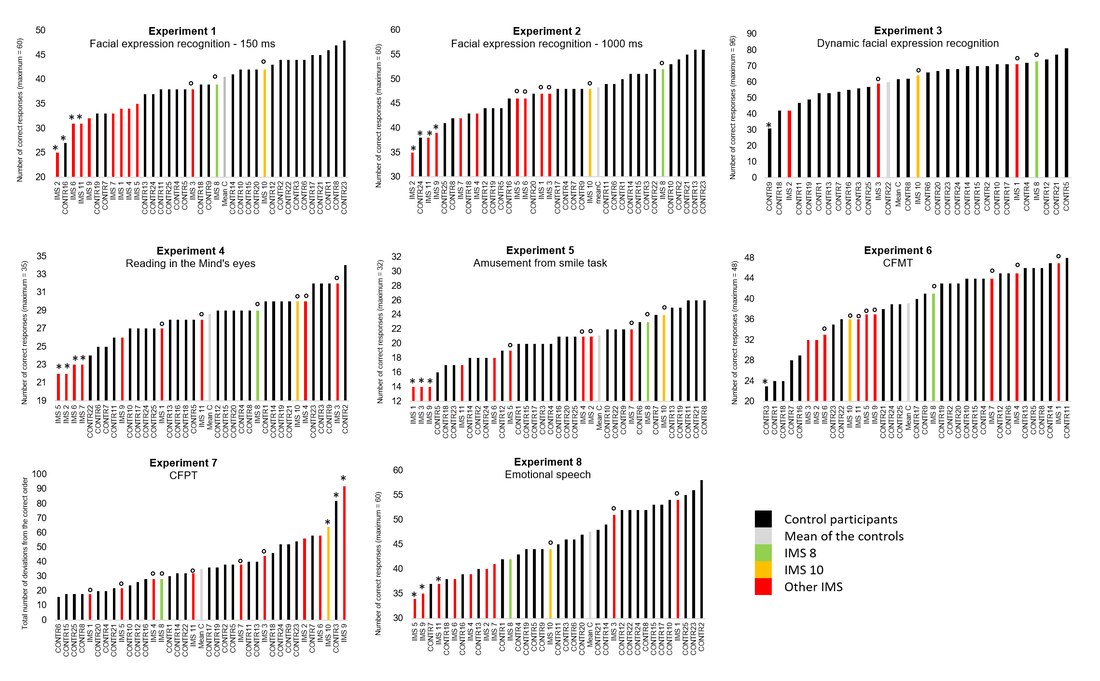

What mechanisms underlie facial expression recognition? A popular hypothesis holds that efficient facial expression recognition cannot be achieved by visual analysis alone but additionally requires a mechanism of motor simulation — an unconscious, covert imitation of the observed facial postures and movements. Here, we first discuss why this hypothesis does not necessarily follow from extant empirical evidence. Next, we report experimental evidence against the central premise of this view: we demonstrate that individuals can achieve normotypical efficient facial expression recognition despite a congenital absence of relevant facial motor representations and, therefore, unaided by motor simulation. This underscores the need to reconsider the role of motor simulation in facial expression recognition.

|

Conceptual processing of action verbs with and without motor representations

February 25, 2020

|

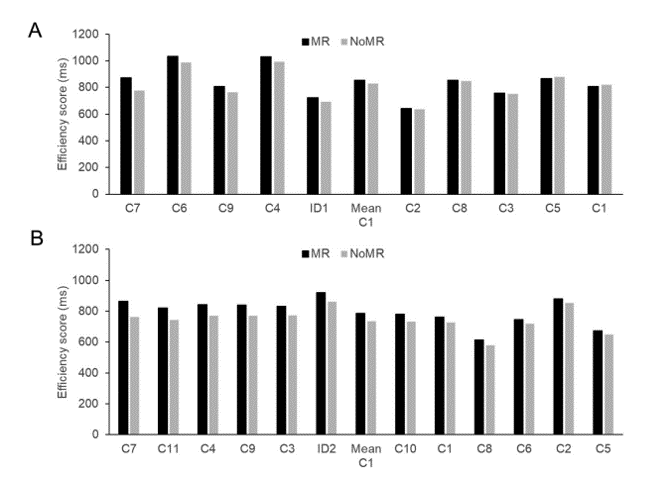

Reading an action verb activates its corresponding motor representation in the reader’s motor cortex, but whether and if so to what extent this activation is relevant for comprehension remains unclear. In this study, we aimed to quantify the contribution of motor representations to the conceptual processing of action verbs by measuring the advantage in speed and accuracy of processing of verbs referring to actions that an individual has previously executed and, therefore, are associated with a motor representation in comparison to verbs referring to actions that this individual has never executed. To do so, we assessed the speed and accuracy of 20 typical participants (Cs on the Figure) and of two participants with atypical motor experience due to congenitally severely reduced upper limbs (ID1 and ID2 on the Figure) in a timed concreteness judgment task. We measured the IDs’ efficiency in processing verbs referring to actions that they had previously executed (e.g., writing; "MR" verbs on the Figure) or not (e.g., shoveling; "NoMR" verbs on the Figure) and compared the efficiency difference between the two verb categories to that found in the Cs, who had previously executed all these actions. This allowed measuring the contribution of motor representations unbiased by confounded low-level, lexical and semantic variables. Although the task was sensitive and the participants’ performance was positively influenced by the richness of the words’ conceptual representations, we found no detectable advantage for words associated with motor representations. These results suggest that motor representations do not contribute to understanding action-related words.

|

Large-scale organization of the hand action observation network in individuals born without hands

August 28, 2018

|

The human high-level visual cortex comprises regions specialized for the processing of distinct types of stimuli, such as objects, animals, and human actions. How does this specialization emerge? Here, we investigated the role of sensorimotor experience in shaping the organization of the action observation network as a window on this question. Observed body movements are frequently coupled with corresponding motor codes, e.g. during monitoring one’s own movements and imitation, resulting in bidirectionally connected circuits between areas involved in body movements observation (e.g., of the hand) and the motor codes involved in their execution. If the organization of the action observation network is shaped by this sensorimotor coupling, then, it should not form for body movements that do not belong to individuals’ motor repertoire. To test this prediction, we used fMRI to investigate the spatial arrangement and functional properties of the hand and foot action observation circuits in individuals born without upper limbs. Multivoxel pattern decoding, pattern similarity, and univariate analyses revealed an intact hand action observation network in the individuals born without upper limbs. This suggests that the organization of the action observation network does not require effector-specific visuomotor coupling.

|

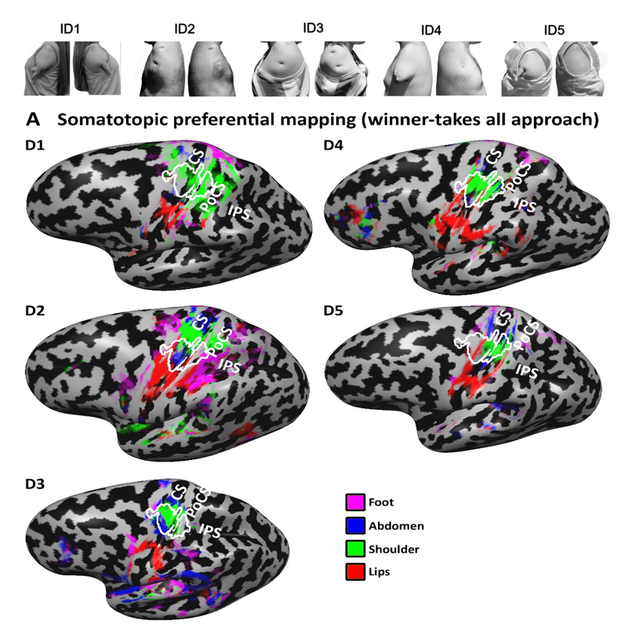

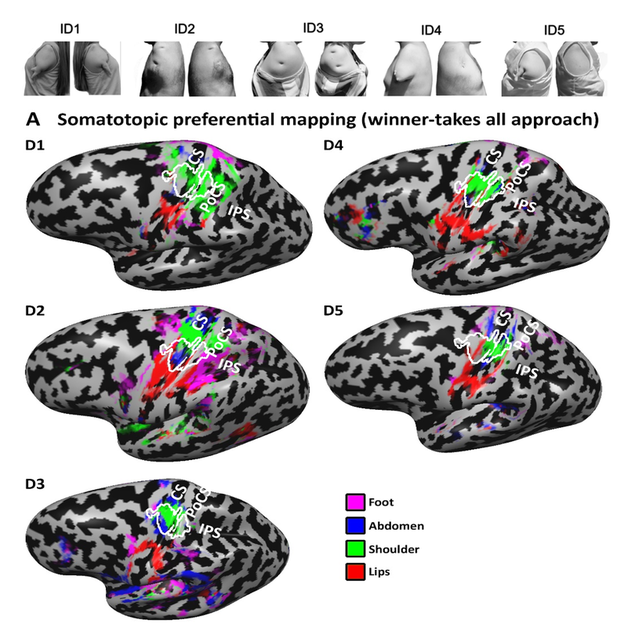

Plasticity based on compensatory effector use in the association but not primary sensorimotor cortex of people born without hands

July 11, 2018

|

What forces direct brain organization and its plasticity? When brain regions are deprived of their input, which regions reorganize based on compensation for the disability and experience, and which regions show topographically constrained plasticity? People born without hands activate their primary sensorimotor hand region while moving body parts used to compensate for this disability (e.g., their feet). This was taken to suggest a neural organization based on functions, such as performing manual-like dexterous actions, rather than on body parts, in primary sensorimotor cortex. We tested the selectivity for the compensatory body parts in the primary and association sensorimotor cortex of people born without hands (dysplasic individuals). Despite clear compensatory foot use, the primary sensorimotor hand area in the dysplasic subjects showed preference for adjacent body parts that are not compensatorily used as effectors. This suggests that function-based organization, proposed for congenital blindness and deafness, does not apply to the primary sensorimotor cortex deprivation in dysplasia. These findings stress the roles of neuroanatomical constraints like topographical proximity and connectivity in determining the functional development of primary cortex even in extreme, congenital deprivation. In contrast, increased and selective foot movement preference was found in dysplasics’ association cortex in the inferior parietal lobule. This suggests that the typical motor selectivity of this region for manual actions may correspond to high-level action representations that are effector-invariant. These findings reveal limitations to compensatory plasticity and experience in modifying brain organization of early topographical cortex compared with association cortices driven by function-based organization.

|

Large-scale organization of the hand action observation network in individuals born without hands

April 23, 2018

|

The human high-level visual cortex comprises regions specialized for the processing of distinct types of stimuli, such as objects, animals, and human actions. How does this specialization emerge? Here, we investigated the role of sensorimotor experience in shaping the organization of the action observation network as a window on this question. Observed body movements are frequently coupled with corresponding motor codes, e.g. during monitoring one’s own movements and imitation, resulting in bidirectionally connected circuits between areas involved in body movements observation (e.g., of the hand) and the motor codes involved in their execution. If the organization of the action observation network is shaped by this sensorimotor coupling, then, it should not form for body movements that do not belong to individuals’ motor repertoire. To test this prediction, we used fMRI to investigate the spatial arrangement and functional properties of the hand and foot action observation circuits in individuals born without upper limbs. Multivoxel pattern decoding, pattern similarity, and univariate analyses revealed an intact hand action observation network in the individuals born without upper limbs. This suggests that the organization of the action observation network does not require effector-specific visuomotor coupling.

|

Limitations of compensatory plasticity: the organization of the primary sensorimotor cortex in foot-using bilateral upper limb dysplasics

March 6, 2018

|

What forces direct brain organization and its plasticity? When a brain region is deprived of its input would this region reorganize based on compensation for the disability and experience, or would strong limitations of brain structure limit its plasticity? People born without hands activate their sensorimotor hand region while moving body parts used to compensate for this ability (e.g. their feet). This has been taken to suggest a neural organization based on functions, such as performing manual-like dexterous actions, rather than on body parts. Here we test the selectivity for functionally-compensatory body parts in the sensorimotor cortex of people born without hands. Despite clear compensatory foot use, the sensorimotor hand area in the dysplasic subjects showed preference for body parts whose cortical territory is close to the hand area, but which are not compensatorily used as effectors. This suggests that function-based organization, originally proposed for congenital blindness and deafness, does not apply to cases of the primary sensorimotor cortex deprivation in dysplasia. This is consistent with the idea that experience-independent functional specialization occurs at relatively high levels of representation. Indeed, increased and selective foot movement preference in the dysplasics was found in the association cortex, in the inferior parietal lobule. Furthermore, it stresses the roles of neuroanatomical constraints such as topographical proximity and connectivity in determining the functional development of brain regions. These findings reveal limitations to brain plasticity and to the role of experience in shaping the functional organization of the brain.

|

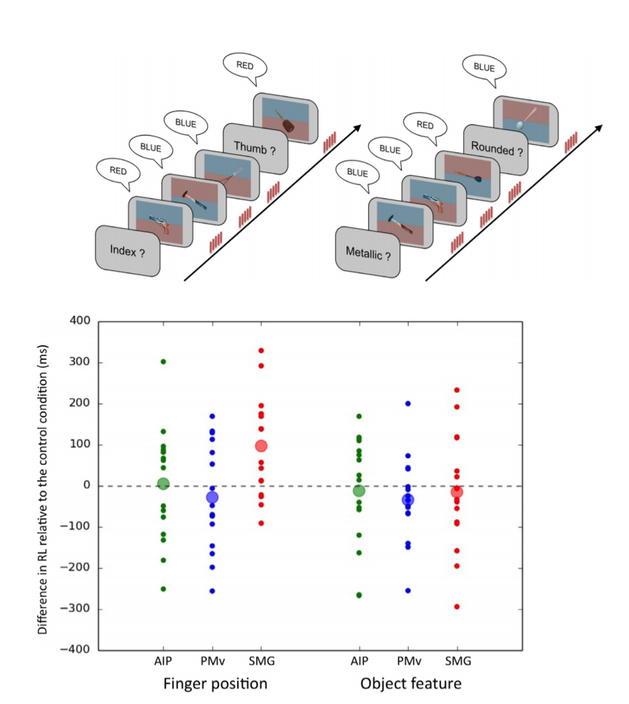

The left supramarginal gyrus contributes to finger positioning for object use: A neuronavigated TMS study.

October 27, 2017

|

In everyday actions, we grasp dozens of different manipulable objects in ways that accommodate their functional use. Neuroimaging studies showed that grasping objects in a way that is appropriate for their use involves a left-lateralized network including the supramarginal gyrus (SMG), the anterior intraparietal area (AIP) and the ventral premotor cortex (PMv). However, because previous works premised their conclusions on tasks requiring action execution, it has remained difficult to discriminate between the areas involved in specifying the position of fingers onto the object from those implementing the motor program required to perform the action. To address this issue, we asked healthy participants to make judgements about pictures of manipulable objects while repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) was applied over the left SMG, AIP, PMv or, as a control, the Vertex. The participants were asked to name the part of the image where the thumb or the index finger was expected to contact the object during its normal utilization or where a given attribute of the same object was located. The two tasks were strictly identical in terms of visual display, working memory demands, and response requirements. Results showed that rTMS over SMG slowed down judgements about finger positioning but not judgements about object attributes. Both types of judgements remained unaffected when rTMS was applied over AIP or PMv. This finding demonstrates that, within the parieto-frontal network dedicated to object use, at least the left SMG is involved in specifying the appropriate position of the thumb and index finger onto the object.

|

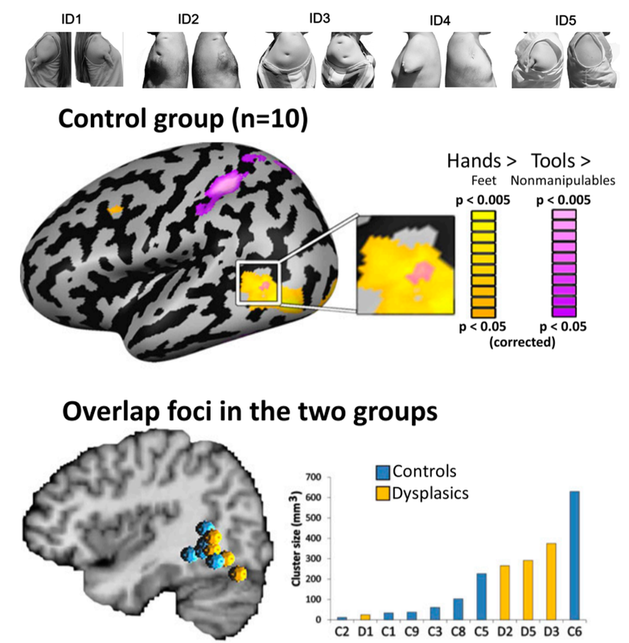

Sensorimotor-independent development of hands and tools selectivity in the visual cortex.

May 2, 2017

|

The visual ventral occipital temporal cortex (VOTC) is composed of several distinct regions specialized in the identification of different object kinds such as tools and bodies. Its organization appears to reflect not only the visual characteristics of the inputs but also the behavior that can be achieved with them. For example, there are spatially overlapping responses for viewing hands and tools, which are likely due to their common role in object-directed actions. How dependent is LOTC organization on object manipulation and motor experience? To investigate this question, we studied five individuals born without hands (individuals with upper limb dysplasia; IDs), who use tools with their feet. Using fMRI, we found the typical selective hand-tool overlap (HTO) not only in typically-developed control participants, but also in four of the five IDs. Functional connectivity of the HTO in the IDs also showed a largely similar pattern as in the controls. The clear preservation of functional organization in the IDs suggests that LOTC specialization is driven largely by inherited connectivity constraints that do not require sensorimotor experience. These findings complement discoveries of intact functional LOTC organization in people born blind, supporting an organization largely independent from any one specific sensory or motor experience.

|

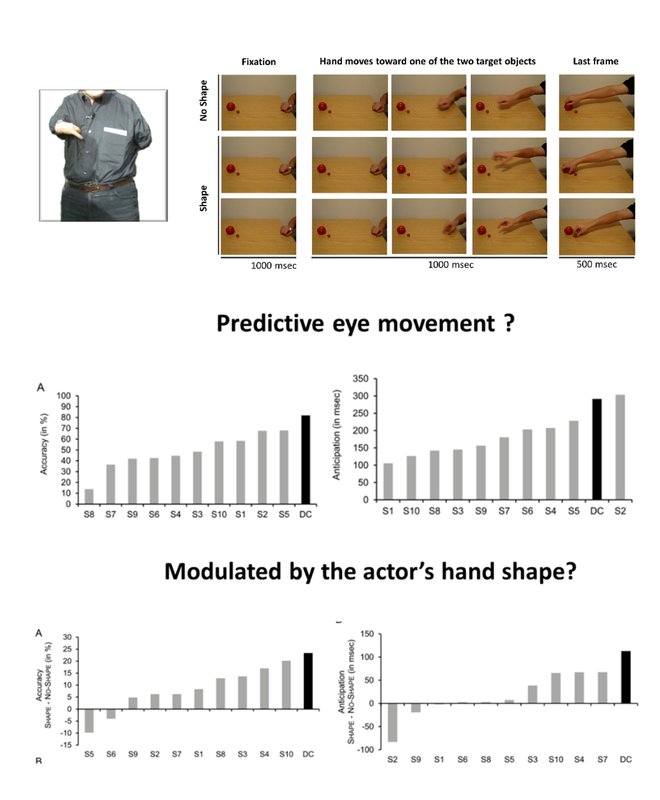

Typical predictive eye movements during action observation without effector-specific motor simulation.

December 21, 2016

|

When watching someone reaching to grasp an object, we typically gaze at the object before the agent’s hand reaches it, that is, we make a “predictive eye movement” to the object. The received explanation is that predictive eye movements rely on a direct matching process by which the observed action is mapped onto the motor representation of the same body movements in the observer’s brain. In this paper, we report evidence that calls for a re-examination of this account. We recorded the eye movements of an individual born without arms (D.C.) when watching an actor reaching for one of two different-sized objects with a power grasp, a precision grasp or a closed fist. D.C. showed typical predictive eye movements modulated by the actor’s hand shape. This finding constitutes existence proof that predictive eye movements during action observation can rely on visual and inferential processes unaided by effector-specific motor simulation.

|

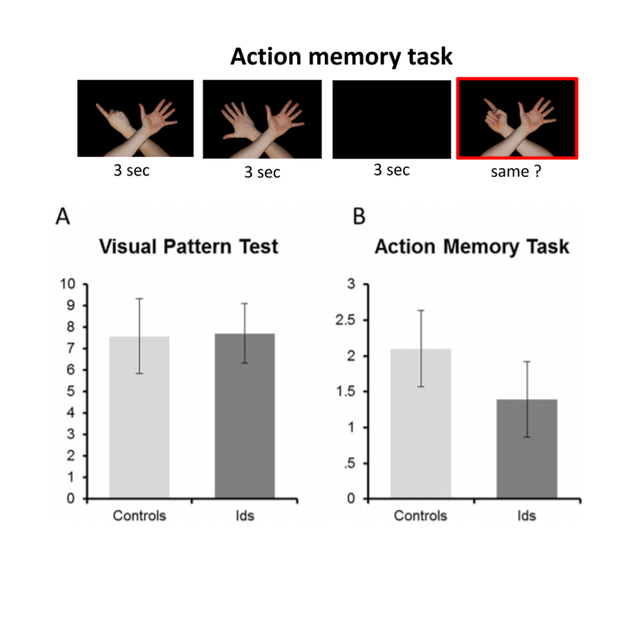

Impaired short-term memory for hand postures in individuals born without hands.

July 29, 2016

|

The psychological and neurobiological processes underlying short-term memory for words and objects have been the focus of very numerous studies and of detailed hypotheses (Baddeley, Eysenck & Anderson, 2014; D’Esposito & Postle, 2015). In contrast, the mechanisms that support the temporary storage of information about other’s actions and body postures in memory remain largely unknown. This study focused on a specific issue related to this question: does short-term memory for body postures rely, at least partly, on imitative motoric processes? We compared the performance of seven individuals born with absent or severely shortened upper limbs and no history of phantom limb sensations (IDs; 5 women; mean age = 40.28), and of 19 typically developed control participants (11 women; mean age = 50.64) in a task measuring visual short-term memory for hand postures and in a task measuring visual short-term memory for non-biological patterns. The results were in line with the hypothesis that imitative motoric processes can support short term memory for body postures: the individuals born without upper limbs have difficulty in keeping pictures of hand postures in memory even for a short duration

|

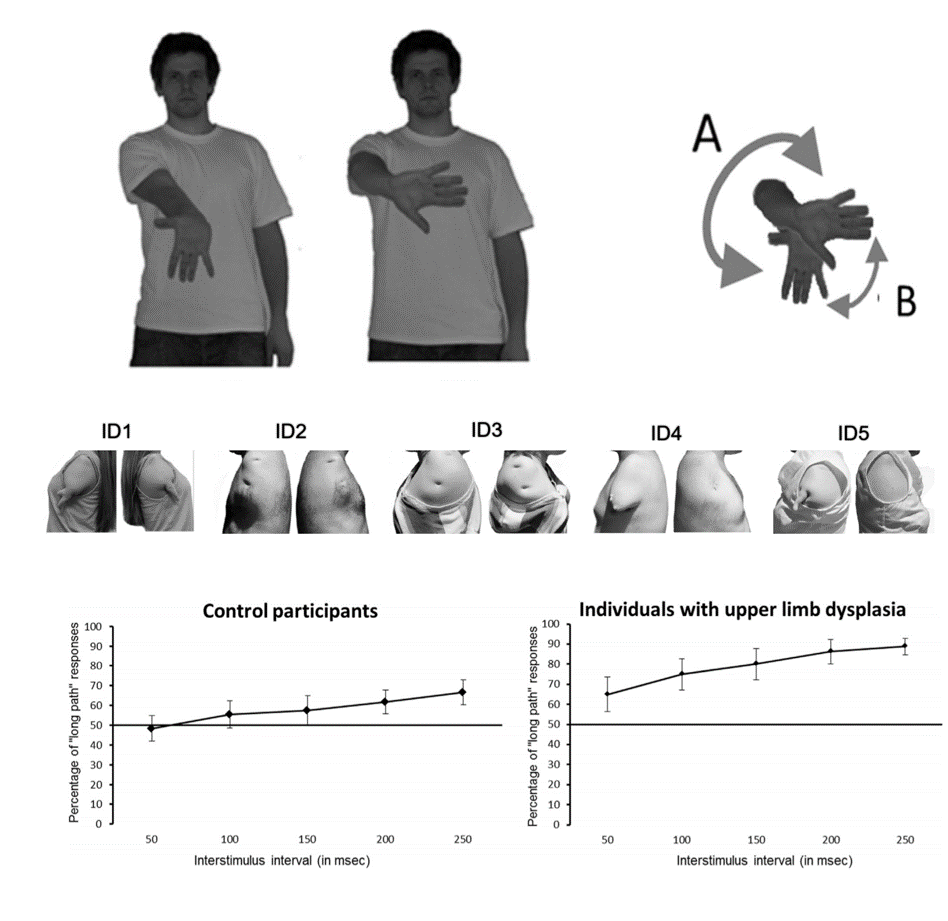

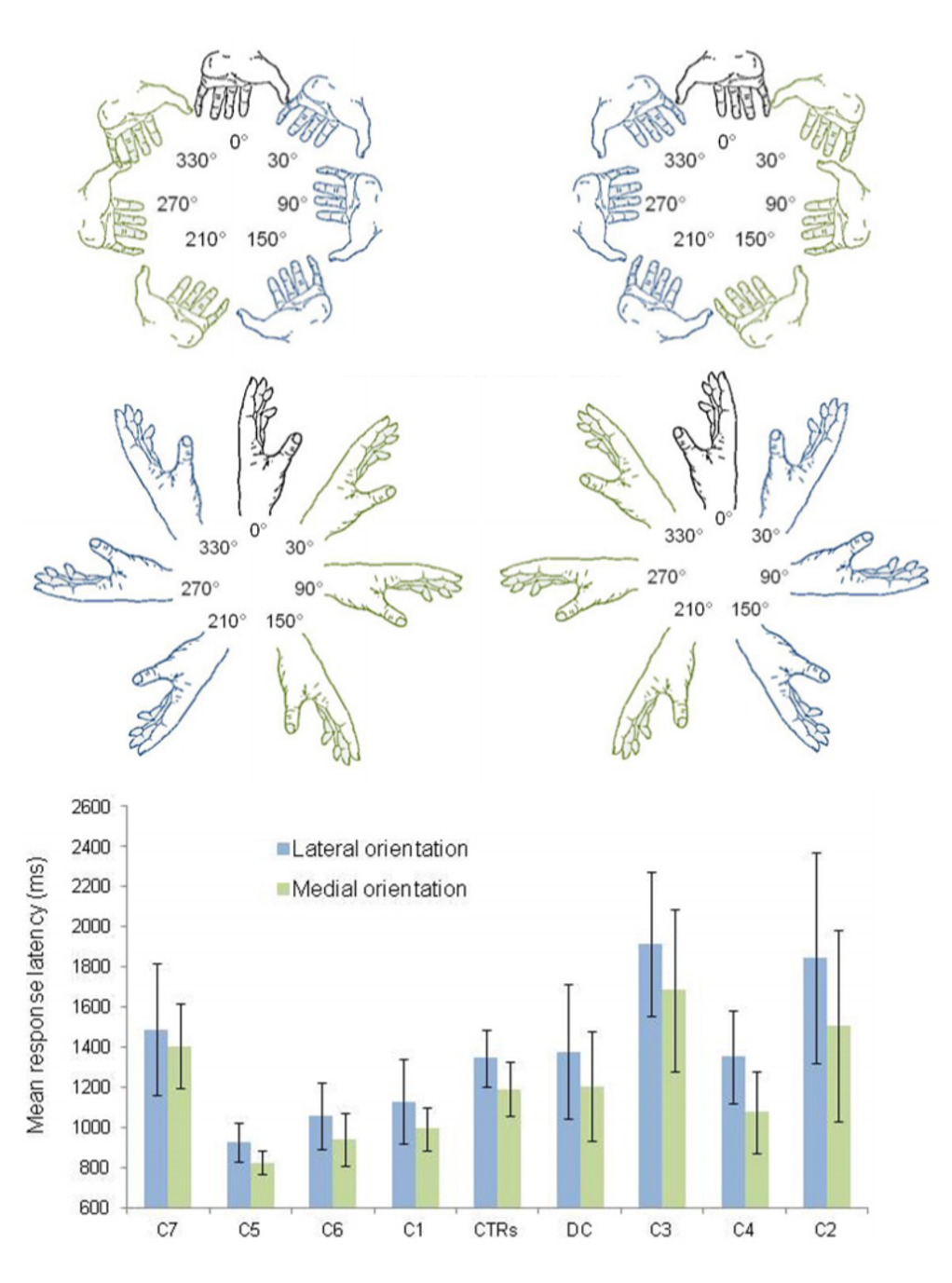

The origin of the biomechanical bias in apparent body movement perception

May 27, 2016

|

The perception of apparent body movement sometimes follows biologically plausible paths rather than paths along the shortest distance as in the case for inanimate objects. For numerous authors, this demonstrates that the somatosensory and motor representations of the observer’s own body support and constrain the perception of others’ body movements. In this paper, we report evidence that calls for a re-examination of this account. We presented an apparent upper limb movement perception task to typically developed participants and five individuals born without upper limbs who were, therefore, totally deprived of somatosensory or motor representations of those limbs. Like the typically developed participants, they showed the typical bias toward long and biomechanically plausible path. This finding suggests that the computations underlying the biomechanical bias in apparent body movement perception is intrinsic to the visual system.

|

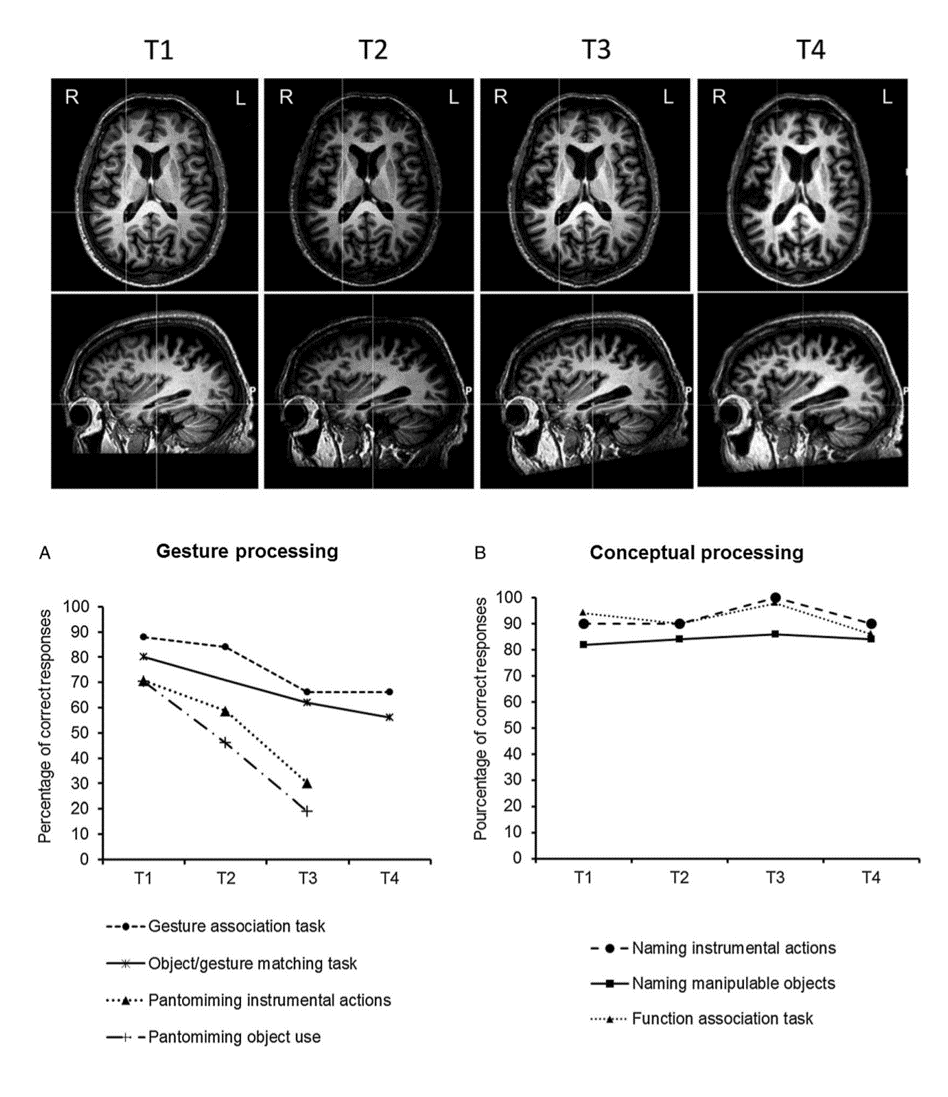

Persistent sparing of action conceptual processing in spite of increasing disorders of action production: A case against motor embodiment of action concepts.

April 29, 2016

|

In this study, we addressed the issue of whether the brain sensorimotor circuitry that controls action production is causally involved in representing and processing action-related concepts. We examined the three-year pattern of evolution of brain atrophy, action production disorders, and action-related concept processing in a patient (J.R.) diagnosed with corticobasal degeneration. During the period of investigation, J.R. presented with increasing action production disorders resulting from increasing bilateral atrophy in cortical and subcortical regions involved in the sensorimotor control of actions (notably, the superior parietal cortex, the primary motor and premotor cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the basal ganglia). In contrast, the patient’s performance in processing action-related concepts remained intact during the same period. This finding indicated that action concept processing hinges on cognitive and neural resources that are mostly distinct from those underlying the sensorimotor control of actions

|

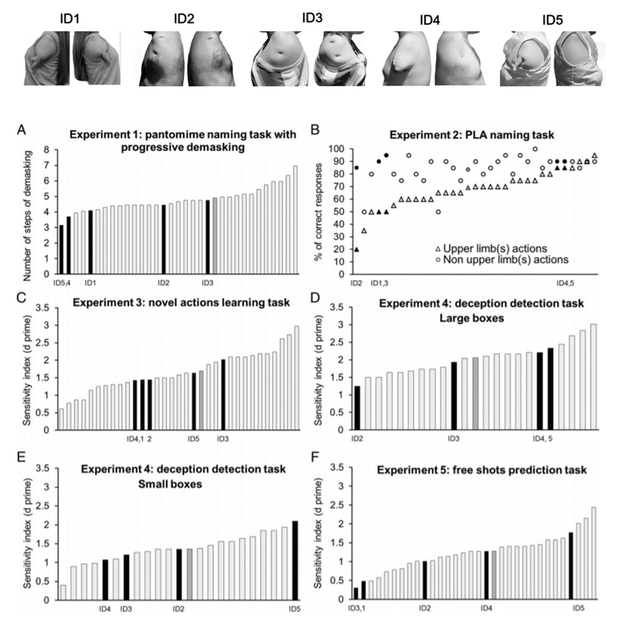

Typical action perception and interpretation without motor simulation

January 5, 2016

|

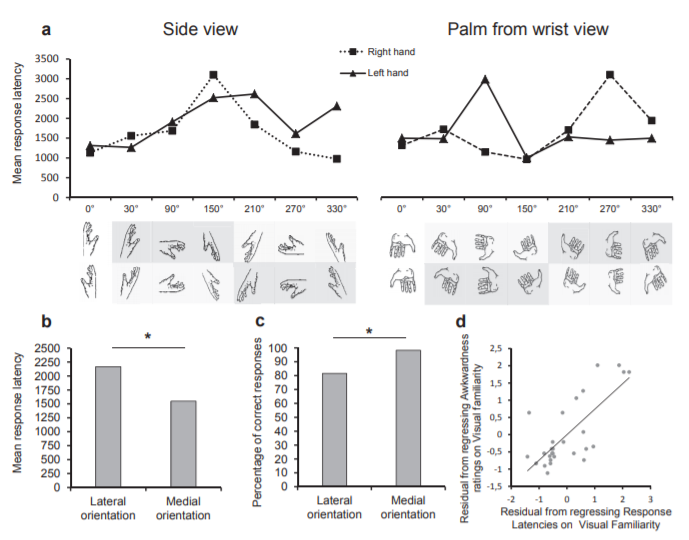

Every day, we interact with people synchronously, immediately understand what they are doing, and easily infer their mental state and the likely outcome of their actions from their kinematics. According to various Motor Simulation Theories of Perception, such efficient perceptual processing of others’ actions cannot be achieved by visual analysis of the movements alone but requires a process of “motor simulation” – an unconscious covert imitation of the observed movements. On this hypothesis, individuals incapable of simulating observed movements in their motor system should have difficulty perceiving and interpreting observed actions. Contrary to this prediction, we found across eight sensitive experiments that individuals born with absent or severely shortened upper limbs (upper limb Dysplasia), despite some variability, could perceive, anticipate, predict, comprehend and memorize upper limb actions, which they cannot simulate, as efficiently as typically developed participants. We also found that, like the typically developed participants, the dysplasic participants systematically perceived the position of moving upper limbs slightly ahead of their real position but only when the anticipated position was not biomechanically awkward. Such anticipatory bias and its modulation by implicit knowledge of the body biomechanical constraints were previously considered as indexes of the crucial role of motor simulation in action perception. Our findings undermine this assumption and the theories that place the locus of action perception and comprehension in the motor system, and invite a shift in the focus of future research to the question of how the visuo-perceptual system represents and processes observed body movements and actions.

|

Typical biomechanical bias in the perception of congenitally absent hands

February 24, 2015

|

There is compelling evidence that our perception of others’ bodies and movements is shaped by several rules and constraints, such as the biomechanics of body movement, originally thought to affect only the control and execution of actual movements. For numerous authors, this demonstrates that the perception of others’ bodies and movements is supported by somatosensory and motor representations of our own body. Accordingly, the presence or absence of effects of body constraints on body perception is increasingly used as an index of, respectively, the integrity or impairment of covert stages of action production in patients with motor execution disabilities. However, these biomechanical constraints biases might simply reflect how the visuo-perceptual system processes and represents human bodies. In favor of this alternative, we found that a person born without upper limbs also showed biomechanical biases when asked to provide perceptual judgments about hand postures.

|

When does action comprehension need motor involvement ? Evidence from upper limb aplasia

November 12, 2013

|

Motor theories of action comprehension claim that comprehending the meaning of an action performed by a conspecific relies on the perceiver’s own motor representation of the same action. According to this view, whether an action belongs to the motor repertoire of the perceiver should impact the ease by which this action is comprehended. We tested this prediction by assessing the ability of an individual (DC) born without upper limbs to comprehend actions involving hands (e.g., throwing) or other body parts (e.g., jumping). The tests used a range of different visual stimuli differing in the kind of information provided. The results showed that DC was as accurate and fast as control participants in comprehending natural video and photographic presentations of both manual and non-manual actions, as well as pantomimes. However, he was selectively impaired at identifying point-light animations of manual actions. This impairment was not due to a difficulty in processing kinematic information per se. DC was indeed as accurate as control participants in two additional tests requiring a fine-grained analysis of an actor’s arm or whole-body movements. These results challenge motor theories of action comprehension by showing that the visual analysis of body shape and motion provides sufficient input for comprehending observed actions. However, when body shape information is sparsely available, motor involvement becomes critical to interpret observed actions. We suggest that, with natural human movement stimuli, motor representations contribute to action comprehension each time visual information is incomplete or ambiguous.

|

Is motor knowledge part and parcel of the concept of manipulable artifacts ? Clues from a case of upper limb aplasia

September 23, 2013

|

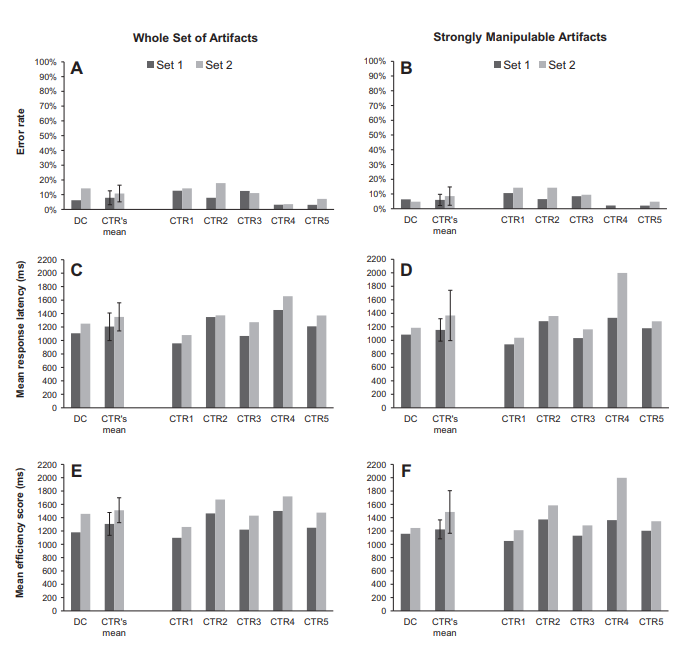

The sensory-motor theory of conceptual representations assumes that motor knowledge of how an artifact is manipulated is constitutive of its conceptual representation. Accordingly, if we assume that the richer the conceptual representation of an object is, the easier that object is identified, manipulable artifacts that are associated with motor knowledge should be identified more accurately and/or faster than manipulable artifacts that are not (everything else being equal). In this study, we tested this prediction by investigating the identification of manipulable artifacts in an individual, DC, who was totally deprived of hand motor experience due to upper limb aplasia. This condition prevents him from interacting with most manipulable artifacts, for which he thus has no motor knowledge at all. However, he had motor knowledge for some of them, which he routinely uses with his feet. We contrasted DC’s performance in a timed picture naming task for manipulable artifacts for which he had motor knowledge versus those for which he had no motor knowledge. No detectable advantage on DC’s naming performance was found for artifacts for which he had motor knowledge compared to those for which he did not. This finding suggests that motor knowledge is not part of the concepts of manipulable artifacts.

|

Effect of biomechanical constraints in the hand laterality judgment task: Where does it come from?

November 1, 2012

|

Several studies have reported that, when subjects have to judge the laterality of rotated hand drawings, their judgment is automatically influenced by the biomechanical constraints of the upper limbs. The prominent account for this effect is that, in order to perform the task, subjects mentally rotate their upper limbs toward the position of the displayed stimulus in a way that is consistent with the biomechanical constraints underlying the actual movement. However, the effect of such biomechanical constraints was also found in the responses of motor-impaired individuals performing the hand laterality judgment (HLJ) task, which seems at odds with the “motor imagery” account for this effect. In this study, we further explored the source of the biomechanical constraint effect by assessing the ability of an individual (DC) with a congenital absence of upper limbs to judge the laterality of rotated hand or foot drawings. We found that DC was as accurate and fast as control participants in judging the laterality of both hand and foot drawings, without any disadvantage for hands when compared to feet. Furthermore, DC’s response latencies (RLs) for hand drawings were influenced by the biomechanical constraints of hand movements in the same way as control participants’ RLs. These results suggest that the effect of biomechanical constraints in the HLJ task is not strictly dependent on “motor imagery” and can arise from the visual processing of body parts being sensitive to such constraints.

|

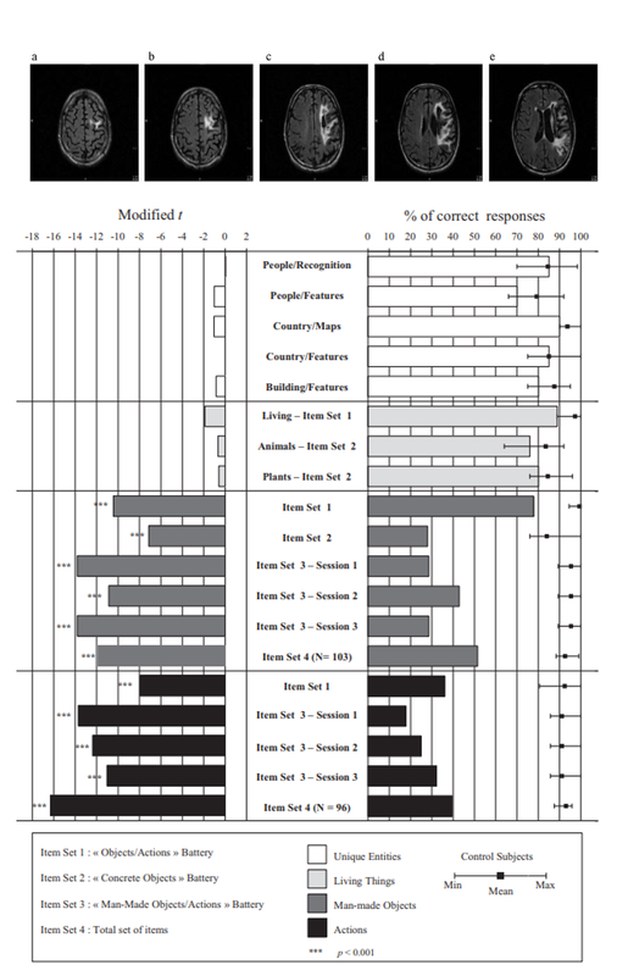

A domain-specific system for representing knowledge of both man-made objects and human actions. Evidence from a case with an association of deficits.

April 17, 2011

|

We report the single-case study of a brain-damaged individual, JJG, presenting with a conceptual deficit and whose knowledge of living things, man-made objects, and actions was assessed. The aim was to seek for empirical evidence pertaining to the issue of how conceptual knowledge of objects, both living things and man-made objects, is related to conceptual knowledge of actions at the functional level. We first found that JJG’s conceptual knowledge of both man-made objects and actions was similarly impaired while his conceptual knowledge of living things was spared as well as his knowledge of unique entities. We then examined whether this pattern of association of a conceptual deficit for both man-made objects and actions could be accounted for, first, by the “sensory/functional” and, second, the “manipulability” account for category-specific conceptual impairments advocated within the Feature-Based-Organization theory of conceptual knowledge organization, by assessing, first, patient’s knowledge of sensory compared to functional features, second, his knowledge of manipulation compared to functional features and, third, his knowledge of manipulable compared to non-manipulable objects and actions. The later assessment also allowed us to evaluate an account for the deficits in terms of failures of simulating the hand movements implied by manipulable objects and manual actions. The findings showed that, contrary to the predictions made by the “sensory/functional”, the “manipulability”, and the “failure-of-simulating” accounts for category-specific conceptual impairments, the patient’s association of deficits for both manmade objects and actions was not associated with a disproportionate impairment of functional compared to sensory knowledge or of manipulation compared to functional knowledge; manipulable items were not more impaired than non-manipulable items either. In the general discussion, we propose to account for the patient’s association of deficits by the hypothesis that concepts whose core property is that of being a mean of achieving a goal – like the concepts of man-made objects and of actions – are learned, represented and processed by a common domain-specific conceptual system, which would have evolved to allow human beings to quickly and efficiently design and understand means to achieve goals and purposes.

|